Parasitic Infections Targets

🧪 SAG1-890T

Source: E.coli

Species: Toxoplasma gondii

Tag: Non

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 45-198 aa

🧪 HSP90-33P

Source: E.coli

Species: Plasmodium falciparum

Tag: Non

Conjugation:

Protein Length:

🧪 ROP1-596T

Source: E.coli

Species: T.gondii

Tag: Non

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 171-574 A.A.

🧪 SAG1-597T

Source: E.coli

Species: T.gondii

Tag: Non

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 49-311 A.A.

🧪 HDAC1-12

Source: Insect Cells

Species: Plasmodium falciparum

Tag: Flag&His

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 1-450 a.a.

🧪 PfLDH-12P

Source: E.coli

Species: Plasmodium falciparum

Tag: His

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 1-316 a.a.

🧪 ROP2-891T

Source: E.coli

Species: T.gondii

Tag: His

Conjugation:

Protein Length: aa186-533

🧪 PPDK-916E

Source: E.coli

Species: Entamoeba Histolytica

Tag: His&SUMO

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 1-342 aa

🧪 MDR1-1315E

Source: Yeast

Species: Entamoeba Histolytica

Tag: His

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 1-114 aa

🧪 MSP1-2506P

Source: E.coli

Species: Plasmodium Falciparum

Tag: His

Conjugation:

Protein Length: 937-1260 aa

Background

What are Parasitic Infections?

Parasitic infections are diseases caused by parasites, a parasite is an organism that lives on or in a host organism and gets its food from or at the expense of its host. There are three main classes of parasites that can cause disease in humans: protozoa, helminths, and ectoparasites.

Protozoa are microscopic, one-celled organisms that can be free-living or parasitic in nature. They are able to multiply in humans, which contributes to their survival and also permits serious infections to develop from just a single organism. They transmit by the fecal-oral route or by arthropod vectors. Worms, which include multicellular parasites such as nematodes, flukes and tapeworms, can be spread through food, water or direct contact. Ectoparasitic animals, such as fleas and lice, that live on the surface of the host's skin.

You can get them from contaminated food or water, a bug bite, or sexual contact. Some parasitic diseases are easily treated and some are not. Prevention is especially important. There are no vaccines for parasitic diseases. Some medicines are available to treat parasitic infections.

What Causes Parasitic Infections?

Parasitic infections can be spread by many ways, including animals, blood, food, insects, and water. There are other factors, such as certain parasitic diseases, such as toxoplasmosis, that can be transmitted through sexual contact. Environmental factors, such as climate and sanitation conditions, as well as socio-economic conditions, all influence the transmission of parasitic diseases and the risk of infection.

- Animals

Pets can carry parasites and pass parasites to people. Proper handwashing can greatly reduce risk. A zoonotic disease is a disease spread between animals and people. Zoonotic diseases can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi. Some of these diseases are very common. For zoonotic diseases that are caused by parasites, the types of symptoms and signs can be different depending on the parasite and the person. Sometimes people with zoonotic infections can be very sick but some people have no symptoms and do not ever get sick. Other people may have symptoms such as diarrhea, muscle aches, and fever.

- Blood

Some parasites can be found in the blood of an infected person and spread to others through contact with the blood of an infected person, such as through blood transfusions or sharing needles or syringes contaminated with blood. Parasitic diseases that can be transmitted by blood include African trypanosomiasis, Babesiosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, malaria and toxoplasmosis. In addition, blood transfusions may also create conditions for parasite transmission. In the United States, the blood supply is screened for some parasites, such as the pathogen of Chagas disease.

- Food

Many parasites can be transmitted through food, including a variety of protozoa and worms. In the United States, the most common foodborne parasites include protozoa such as cryptosporidium, Giardia, cyclospora, and Toxoplasma. Nematodes such as trichinella spiralis and anisakis; As well as tapeworms such as Double disc fluke and Tapeworm. Some foods are contaminated by food service workers who practice poor hygiene or who work in unsanitary facilities.

- Water

Parasites may be present in natural water sources. During outdoor activities, water should be treated before drinking to avoid getting sick. Globally, contaminated water sources can cause severe pain, disability and even death. Common global water-related diseases include guinea worm disease, schistosomiasis, amebiasis, cryptosporidiosis and Giardiasis.

- Insects

Insects can act as mechanical vectors, meaning that the insect can carry an organism but the insect is not essential to the organism's life cycle. Insects can also serve as obligatory hosts where the disease-causing organism must undergo development before being transmitted. Vector-borne transmission of disease can take place when the parasite enters the host through the saliva of the insect during a blood meal (for example, malaria), or from parasites in the feces of the insect that defecates immediately after a blood meal (for example, Chagas disease). Parasites transmitted by insects often circulate in the blood of the host, with the parasite residing in and damaging organs or other parts of the body.

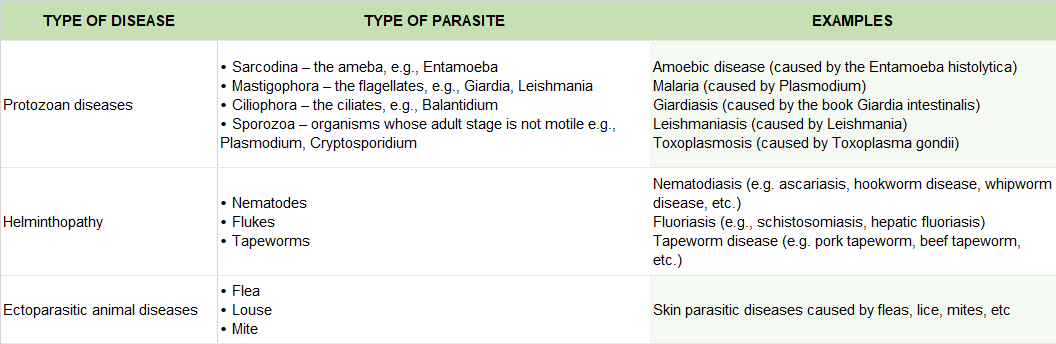

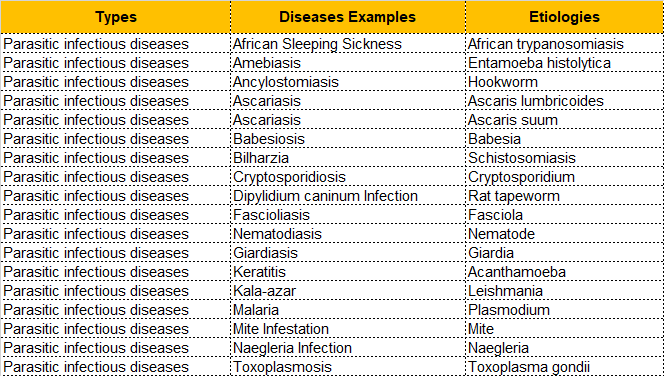

What are the Types of Parasitic infections?

From the species of parasites to distinguish the types of disease, can be divided into the following categories:

As for some common parasitic diseases, we have mapped them to the parasites that cause these diseases, and sorted out a table that can be referred to. The results are as follows:

Symptoms of Parasitic Infections

The symptoms of parasitic diseases vary, depending on the species of parasite, the organ it infects, and the immune response of the host. Here are some common symptoms:

Fever: A common symptom of many parasitic diseases.

Anemia: The mechanism of anemia caused by different parasites is also different.

Diarrhea: One of the most common symptoms of parasitic infection.

Anaphylaxis: A type of hypersensitivity reaction common in the host after parasitic infection.

Malnutrition and developmental disorders: Parasitic infections often cause malnutrition or kwashiorkor.

Large liver and other liver damage: an important pathological consequence of many parasitic diseases.

Splenomegaly: Can lead to hypersplenism.

Skin lesions: May present as a rash or nodular skin lesions.

Central nervous system damage: serious clinical consequences.

Eosinophilia: Eosinophilia in peripheral blood and local tissues is a common clinical phenomenon in many worm infections.

In addition, some specific parasitic diseases may have other symptoms, such as:

Ascariasis and whipworm disease may present paroxysmal periumbilical pain, dyspepsia and other symptoms. Amebiasis may cause abdominal pain and fishy, smelly diarrhea. Hookworm disease may cause anemia, pale face and other symptoms. Toxoplasmosis may be associated with unexplained miscarriage and premature birth. Malaria may cause intermittent chills, fever and other symptoms.

How to Treat Parasitic Infections?

Before starting treatment, it is necessary to confirm whether it is a parasitic infection. Many kinds of lab tests are available to diagnose parasitic diseases. For examples, the use of etiological tests, such as fecal smears, peripheral blood smears, and other biopsies or puncture tests, to identify parasitic diseases in body fluids or secretions. Intradermal tests and serum immune tests, such as indirect erythrocyte agglutination test, indirect fluorescent antibody technique and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, are used to detect specific antibodies produced by the body. And molecular biology examination and imaging examination.

Treatment for parasitic diseases depends on the type of infection, its severity, and the overall health of the patient. At the same time, measures to prevent reinfection, such as improving sanitation, controlling transmission routes and strengthening health education, are equally important in preventing the recurrence and spread of the disease.

Drug treatment: mainly to eliminate and remove parasites, the use of effective deworming drugs for treatment. According to the different parasite species, choose the corresponding treatment plan. For example, the anti-malarial drug artemisinin is used to treat malaria, and metronidazole and tinidazole are used to treat amebiasis and trichomoniasis.

Supportive therapy: When the infection is severe and the body condition is poor, supportive therapy can be given, such as nutritional support and respiratory function support. Surgery should be performed in time when there is local severe infection or other surgical complications.

Case Study

Case Study 1: Recombinant Human hookworm ASP2 protein

cDNAs encoding 2 Ancylostoma-secreted proteins (ASPs), Ancylostoma ceylanicum (Ay)-ASP-1 and Ay-ASP-2, were cloned from infective third-stage larvae (L3) of the hookworm A. ceylanicum and were expressed as soluble recombinant fusion proteins secreted by the yeast Pichia pastoris. The recombinant fusion proteins were purified, adjuvant formulated, and injected intramuscularly into hamsters. Hamsters vaccinated either by oral vaccination with irradiated L3 (irL3) or by injections of the adjuvants alone served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Anti-ASP-1 and anti-ASP-2 antibody titers exceeded 1:100000. Each vaccinated hamster was challenged orally with 100 L3. Two groups of vaccinated hamsters exhibited significant reductions in adult hookworm burdens, compared with control hamsters. The hookworms recovered from the hamsters vaccinated with ASP-2 plus Quil A were reduced in length. Splenomegaly, which was observed in control hamsters, was not seen in hamsters vaccinated with either irL3 or ASP-2 formulated with Quil A.

Fig1. Total IgG titers in serum from golden Syrian hamsters vaccinated with Ay-ASP-2. (Gaddam Narsa Goud, 2004)

Case Study 2: Recombinant Entamoeba Histolytica PPDK Protein

Adverse effects and resistance to metronidazole have motivated the search for new antiamoebic agents against Entamoeba histolytica. Control of amoeba growth may be achieved by inhibiting the function of the glycolytic enzyme and pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK). In this study, we screened 10 compounds using an in vitro PPDK enzyme assay. These compounds were selected from a virtual screening of compounds in the National Cancer Institute database. The antiamoebic activity of the selected compounds was also evaluated by determining minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and IC50 values using the nitro-blue tetrazolium reduction assay. Seven of the 10 compounds showed inhibitory activities against the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)/inorganic phosphate binding site of the ATP-grasp domain.

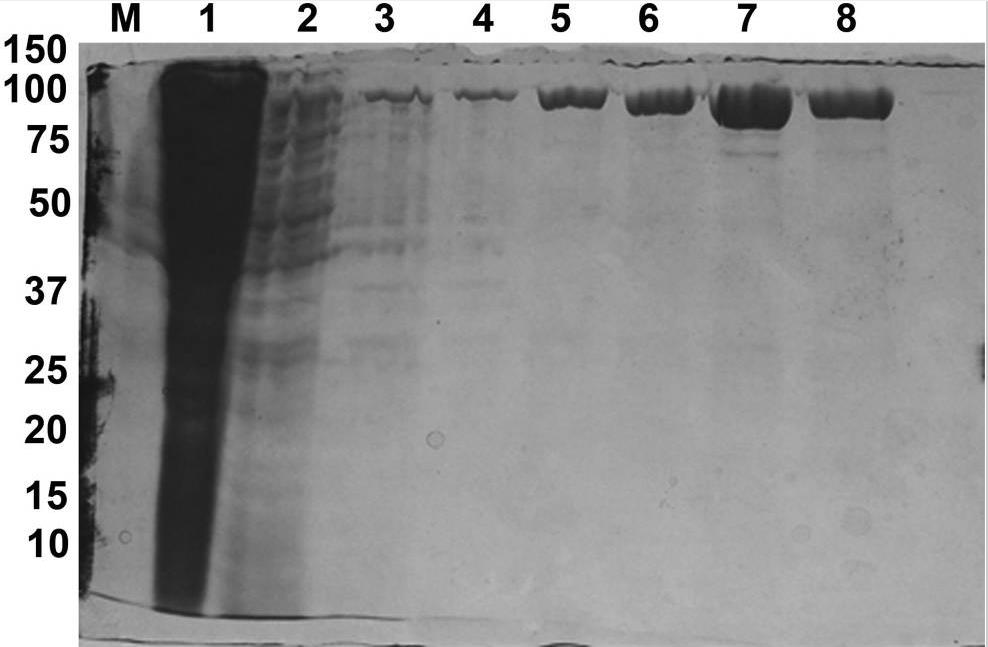

Fig2. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of rPPDK purification. (Syazwan Saidin, 2017)

Case Study 3: Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum FKBP35 protein

Parasites resistant to nearly all antimalarials have emerged and the need for drugs with alternative modes of action is thus undoubted. Whilst there is considerable interest in targeting PfFKBP35 with small molecules, a genetic validation of this factor as a drug target is missing. Here, researchers show that limiting PfFKBP35 levels are lethal to P. falciparum and result in a delayed death-like phenotype that is characterized by defective ribosome homeostasis and stalled protein synthesis. The data furthermore suggest that FK506, unlike the action of this drug in model organisms, exerts its antiproliferative activity in a PfFKBP35-independent manner and, using cellular thermal shift assays, they identify putative FK506-targets beyond PfFKBP35.

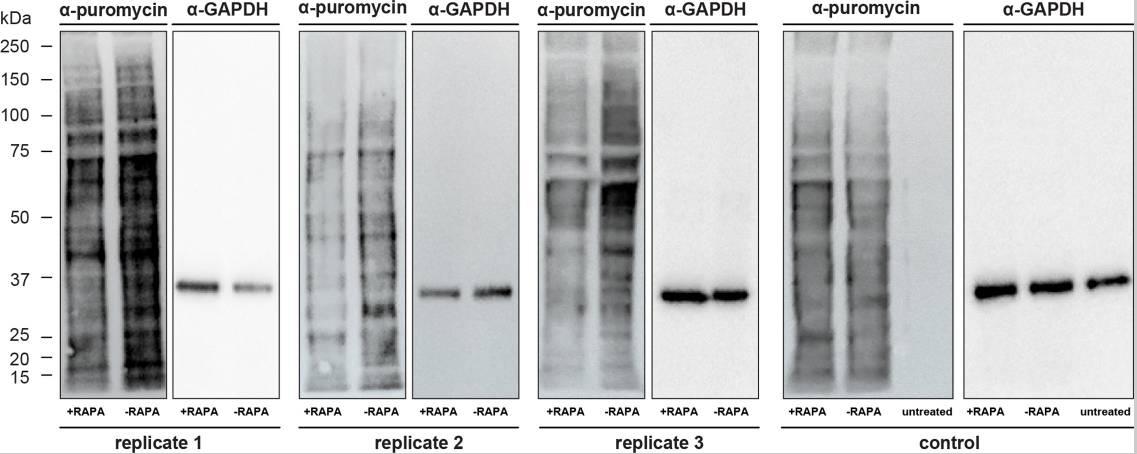

Fig3. Assessment of translation rates of FKBP35KO and FKBP35WT using SUnSET. (Basil T Thommen, 2023)

Related Resources

Parasitic infections, although effectively controlled in many areas, are still a public health problem that cannot be ignored globally. By raising awareness of personal hygiene, improving living conditions, and ensuring food safety and clean water, we can significantly reduce the risk of infection. At the same time, timely medical intervention and targeted treatment are key to helping infected individuals recover. Let us work together to further reduce the incidence of parasitic infections, improve the quality of life and contribute to a healthier world through scientific approaches and ongoing education.

-402V.jpg)