Detergents for Protein Purification: A Comprehensive Resource Guide

The Critical Role of Detergents in Protein Purification

The purification of membrane proteins represents one of the most significant challenges in modern biochemistry and structural biology. These proteins, which constitute approximately 30% of the proteome and mediate essential functions ranging from signal transduction to molecular transport, are embedded within the hydrophobic environment of lipid bilayers. Their extraction and stabilization in aqueous solution demands sophisticated chemical tools that can disrupt native membranes while preserving delicate protein structures. Detergents, with their unique amphiphilic architecture featuring both hydrophobic tails and hydrophilic head groups, serve as indispensable molecular chaperones in this process. They spontaneously assemble into micellar structures that encapsulate the transmembrane domains of proteins, forming stable detergent-protein complexes (DPCs) that enable purification and analysis. However, this solubilization process requires a delicate balancing act—achieving efficient membrane disruption while maintaining the native conformation and functional activity of the target protein. The evolution of detergent technology, from harsh surfactants to rationally designed mild agents, has revolutionized our ability to study these previously intractable molecules, making them accessible to detailed biochemical, biophysical, and structural investigation.

The historical development of detergents for protein purification reflects a growing appreciation for the nuanced requirements of different downstream applications. Early work relied heavily on strong ionic surfactants that excelled at membrane dissolution but sacrificed protein integrity, limiting studies to denatured states suitable only for analytical techniques like SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry. The field gradually shifted toward gentler non-ionic agents that preserved native structure, enabling the crystallization of membrane proteins and eventually the cryo-electron microscopy revolution. Today, researchers have access to a sophisticated toolkit of detergents spanning the spectrum from harsh to mild, each with distinct physicochemical properties tailored to specific experimental goals. This resource guide provides a comprehensive framework for understanding these molecules, their mechanisms of action, and strategic deployment in protein purification workflows.

Classification of Detergents: A Systematic Framework

Understanding detergent classification is fundamental to intelligent selection. The most fundamental division among detergents is based on the net charge of their hydrophilic head groups, which profoundly influences their interaction with proteins and downstream compatibility.

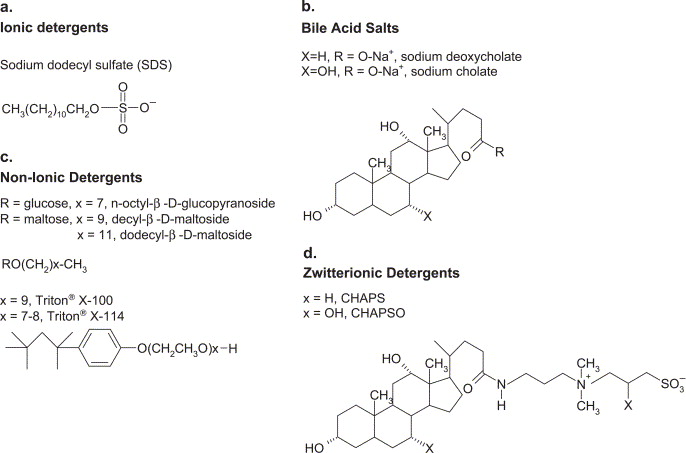

Fig.1. Classification of detergents (Seddon, A. M., et al. 2004)

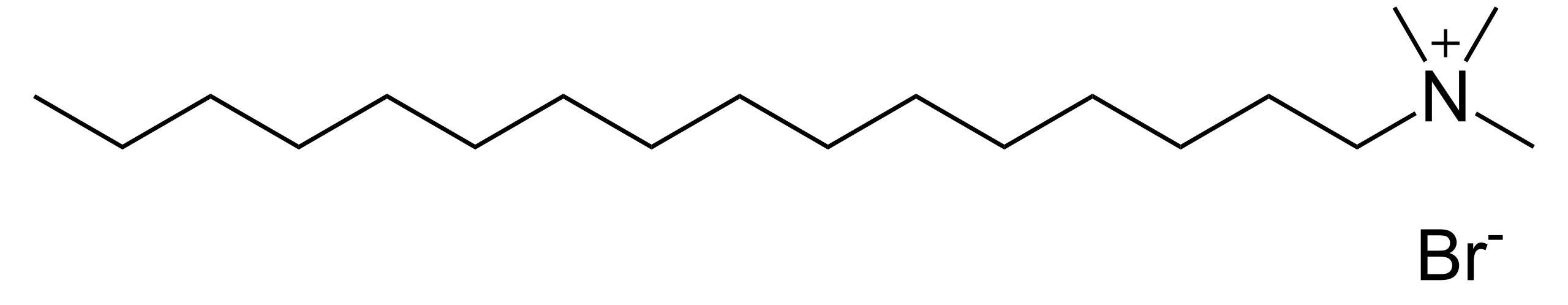

Fig.1. Classification of detergents (Seddon, A. M., et al. 2004)Ionic detergents, which carry a formal positive or negative charge in solution, represent the most aggressive class of solubilizing agents. This category includes anionic surfactants like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and the bile acid salts, as well as cationic agents such as cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB). These molecules excel at disrupting lipid-lipid and protein-lipid interactions through electrostatic repulsion, but this same charge-mediated mechanism makes them prone to denaturing proteins and interfering with chromatographic separations. Their strong binding to protein surfaces can mask natural charges essential for ion-exchange chromatography and may disrupt quaternary structure through electrostatic repulsion between subunits.

In contrast, non-ionic detergents feature neutral, uncharged head groups typically composed of polyhydroxyl moieties or polyethylene glycol units. This class includes the widely used alkyl maltosides and glucosides such as dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), as well as polyoxyethylene detergents like Triton X-100 and Tween-20. The absence of net charge makes these agents considerably milder, preserving native protein structure, oligomeric state, and functional activity. They are generally compatible with all forms of chromatography and spectroscopic analysis, making them the preferred choice for structural and functional studies. However, their mild nature sometimes results in lower extraction efficiency, particularly for proteins embedded in dense lipid microdomains or those forming tight complexes with lipids. Zwitterionic detergents occupy an intermediate position, containing both positive and negative groups that result in no net charge but retain some electrostatic character. CHAPS, CHAPSO, and LDAO exemplify this class, offering solubilization power approaching ionic detergents while maintaining better compatibility with ion-exchange chromatography and preserving more native structure than their ionic counterparts.

Beyond charge-based classification, detergents can be categorized by their denaturing potential, which correlates strongly but not exclusively with charge type.

Denaturing detergents, predominantly ionic surfactants, disrupt not only the membrane but also the protein's secondary and tertiary structure, rendering them suitable only for analytical applications where native conformation is not required.

Non-denaturing detergents, primarily non-ionic and zwitterionic, preserve protein folding and are essential for functional reconstitution and structural determination. Special categories include the bile acid salts, which possess a unique steroid ring structure that creates facial amphiphilicity—the hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces are oriented on opposite sides of the rigid planar molecule. This architecture provides milder disruption than linear-chain detergents. The newest generation includes neopentyl glycol detergents like LMNG, featuring branched hydrophobic tails and dual carbohydrate head groups that create exceptionally stable micellar environments, and oligoglycerol detergents (OGDs) offering tunable properties through variable numbers of glycerol units.

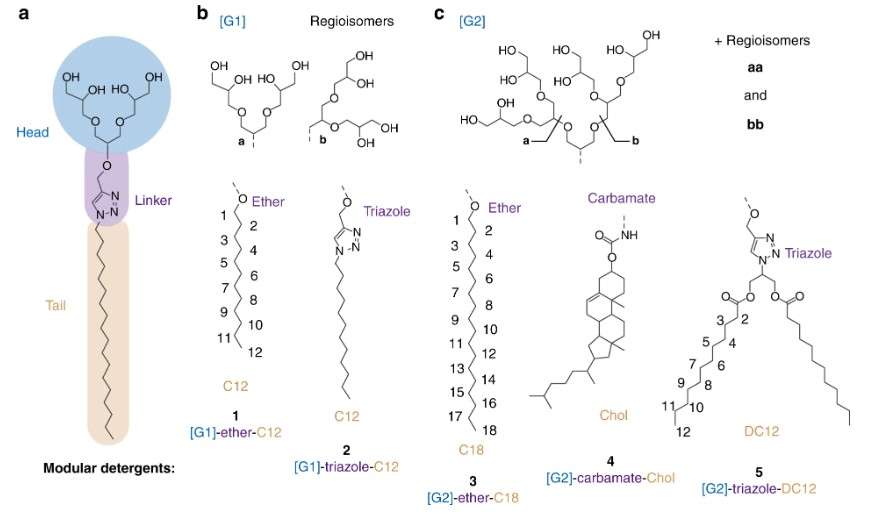

Fig. 2: Describing the modular architecture of OGDs. (Urner, L. H. et al. 2020)

Fig. 2: Describing the modular architecture of OGDs. (Urner, L. H. et al. 2020)a The molecular architecture of OGDs comprises a hydrophilic head, a hydrophobic tail, and a connecting linker. b, c OGD regioisomer mixtures based on first-generation [G1] or second-generation [G2] triglycerol are composed of different head group regioisomers (top), linker, and tail structures (bottom). The modular OGD architecture allows this detergent family to be optimized for protein purification, charge reduction, and lipid co-purification.

Mechanism of Action: Molecular Principles

The action of detergents on biological membranes follows a well-defined sequence of molecular events governed by fundamental physicochemical principles. The process begins when detergent monomers, present at concentrations below the critical micellar concentration (CMC), partition into the lipid bilayer by inserting their hydrophobic tails between the acyl chains of phospholipids. This insertion causes membrane thinning and increases lateral pressure, creating curvature strain. As the detergent concentration rises toward the CMC, the membrane becomes saturated with detergent molecules, typically reaching a detergent-to-lipid ratio of 1:1 to 3:1. At this saturation point, the bilayer undergoes a cooperative transition, fragmenting into mixed detergent-lipid micelles that encapsulate membrane proteins in their native-like environment. This solubilization phase produces stable detergent-protein complexes where the detergent forms a toroidal belt around the transmembrane region, shielding hydrophobic surfaces from aqueous exposure while the extramembraneous domains remain in solution.

The critical micellar concentration serves as the most important parameter in detergent selection and application. CMC values range over three orders of magnitude, from ultra-low values around 0.01 mM for LMNG to 8.2 mM for SDS and 25 mM for octyl glucoside (OG). In practice, efficient membrane solubilization requires detergent concentrations above the CMC to ensure sufficient micellar mass, typically in the range of 1-3 times the CMC. However, purification steps often benefit from reducing the concentration below the CMC to minimize free monomer interference with chromatography and to facilitate detergent removal. The CMC is not a fixed constant but varies with experimental conditions including temperature, ionic strength, pH, and the presence of chaotropic agents. For ionic detergents, increasing salt concentration screens charge repulsion between head groups, lowering the CMC. For non-ionic detergents, temperature changes dramatically affect CMC, with many exhibiting cloud point phenomena where phase separation occurs above a critical temperature.

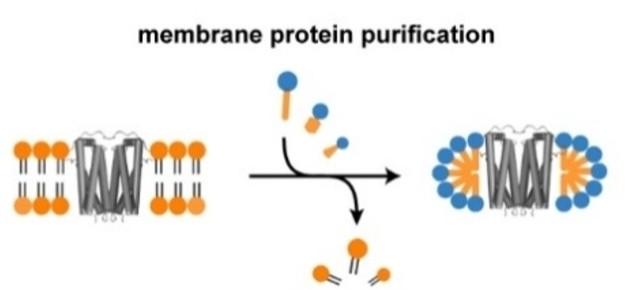

Fig3. Membrane protein purification

Fig3. Membrane protein purificationHead group charge fundamentally alters the disruption mechanism. Ionic detergents exert strong electrostatic forces on the membrane surface, with anionic surfactants repelling negatively charged phospholipid head groups and cationic agents interacting strongly with acidic lipids. This charge-mediated disruption accelerates solubilization kinetics but also increases the risk of protein denaturation through electrostatic competition with native protein-lipid contacts. In contrast, non-ionic detergents rely purely on hydrophobic matching and steric effects, inserting more gently and preserving the delicate balance of forces maintaining protein structure. The hydrophobic tail length, typically ranging from C8 to C16, must complement the thickness of the protein's transmembrane domain—a mismatch can induce non-native curvature stress or fail to fully encapsulate the hydrophobic region. The aggregation number, or number of detergent monomers per micelle, directly impacts downstream applications, with small micelles (<20 monomers) providing better SEC resolution while large micelles (>50 monomers) offer superior protein stability but complicate size-based separations.

Ionic Detergents: High Efficiency, High Risk

Ionic detergents represent the most powerful but potentially destructive class of solubilizing agents, distinguished by their charged head groups that enable aggressive membrane disruption through combined hydrophobic and electrostatic mechanisms. Among anionic detergents, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) stands as the archetypal strong denaturant. Its C12 alkyl chain inserts efficiently into membranes while the sulfate head group imparts a uniform negative charge that coats protein surfaces. This coating disrupts secondary and tertiary structure by overcoming intramolecular hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, rendering SDS ideal for applications where complete denaturation is desired or acceptable. In proteomics and mass spectrometry workflows, SDS achieves extraction efficiencies exceeding 95% and ensures complete denaturation for tryptic digestion and peptide analysis. Its low cost and well-defined properties make it economical for large-scale membrane proteome mapping. However, these advantages come at the cost of irreversible structural damage, making SDS incompatible with functional assays, ligand binding studies, or any downstream application requiring native conformation. Furthermore, its strong charge prevents binding to ion-exchange resins and interferes with most forms of chromatography, limiting purification options to methods like filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) followed by mass spectrometry.

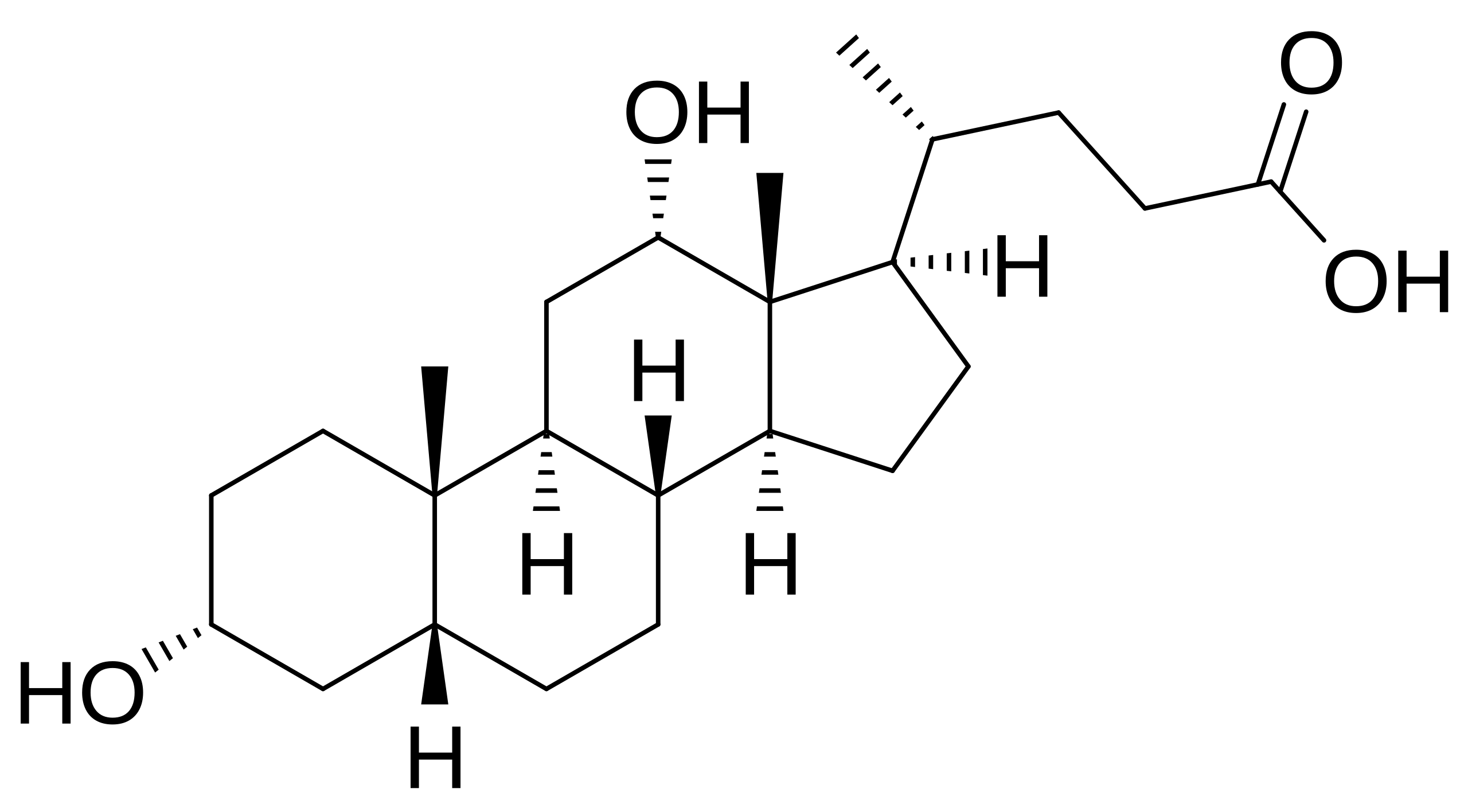

The bile acid salts—cholate, deoxycholate (DOC), and their taurine-conjugated derivatives—offer a more nuanced approach within the anionic detergent family. Their unique steroid ring structure creates facial amphiphilicity, where one face of the rigid planar molecule is hydrophobic while the opposite face bears hydroxyl groups and a carboxylate head group. This architecture provides milder disruption than linear-chain detergents while retaining the high CMC values (4-6 mM) that facilitate removal by dialysis or dilution. Deoxycholate, in particular, has proven valuable for functional extraction of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and transporters, capable of preserving ligand binding activity when used at optimized concentrations of 2-4 mM at low temperature. The pH sensitivity of carboxylate groups requires careful buffer control, as protonation below pH 7 reduces solubilization efficacy. While generally compatible with immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), bile salts can still disrupt quaternary structure and may strip essential boundary lipids, necessitating supplementation with synthetic lipids to maintain activity.

Fig.4. Deoxycholic_acid

Fig.4. Deoxycholic_acidCationic detergents, exemplified by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), occupy a more specialized niche. The quaternary ammonium head group remains fully charged across the entire pH range, providing consistent strong interaction with acidic phospholipids abundant in membranes like the mitochondrial inner leaflet. This property makes CTAB uniquely effective for extracting proteins from lipid environments rich in cardiolipin and phosphatidic acid. However, the same charge characteristics create severe drawbacks: CTAB binds irreversibly to silica-based chromatography resins, forms insoluble complexes with nucleic acids, and its extremely low CMC (0.9 mM) makes removal exceptionally difficult. Practical application requires immediate post-extraction removal using hydrophobic adsorbents like Bio-Beads SM-2, followed by reconstitution in milder detergents. The narrow utility and significant handling challenges relegate CTAB to scenarios where specific lipid compositions justify the additional complexity.

Fig.5. Cetyltrimethyl_ammonium_bromide (CTAB)

Fig.5. Cetyltrimethyl_ammonium_bromide (CTAB)Non-Ionic Detergents: The Gold Standard for Native Purification

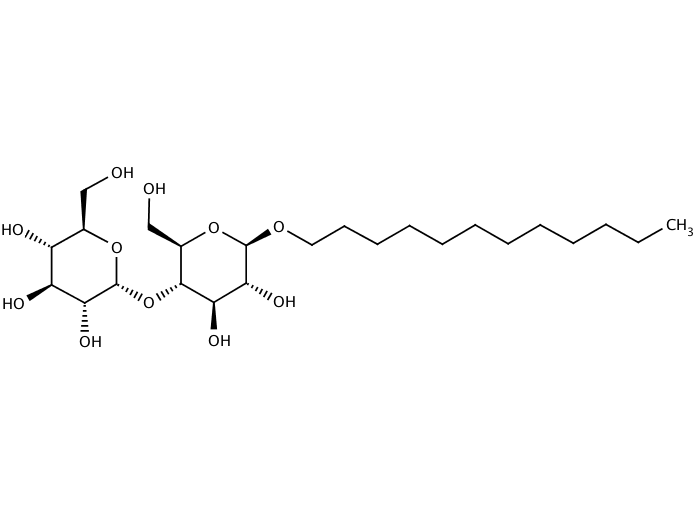

Non-ionic detergents have emerged as the preferred tools for preserving membrane protein structure and function during purification, thanks to their uncharged hydrophilic head groups that minimize electrostatic interference with protein surfaces. Among these, the alkyl glycosides represent the most widely used and reliable class. Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) serves as the benchmark detergent for structural and functional studies, combining exceptional protein stabilizing properties with reasonable availability. Its extremely low CMC of 0.17 mM ensures that DPCs remain stable even during extensive dialysis or dilution, while its large micelle size (molecular weight ~50 kDa with aggregation number ~98) provides robust shielding of transmembrane domains. DDM has enabled countless high-resolution structures of GPCRs, ion channels, and transporters, particularly when supplemented with cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) to better mimic the native lipid environment. The main drawbacks are cost—typically $50-100 per gram—and the very low CMC that complicates removal when desired. Nevertheless, for high-value targets where functional integrity is paramount, DDM remains the first-line choice.

Fig.6. Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM)

Fig.6. Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM)Shorter-chain alkyl glycosides like octyl-β-D-glucoside (OG) and undececyl-β-D-maltoside (UDM) offer complementary properties. OG's high CMC of 25 mM allows rapid removal by simple dilution or brief dialysis, making it ideal for applications requiring transient solubilization. However, the shorter C8 chain provides less shielding, resulting in a harsher solubilization environment that can destabilize some proteins. This trade-off between ease of removal and protein stability exemplifies the decision-making process in detergent selection. UDM, with its C11 chain, offers an intermediate option, providing better stability than OG while retaining higher CMC than DDM for easier removal after purification.

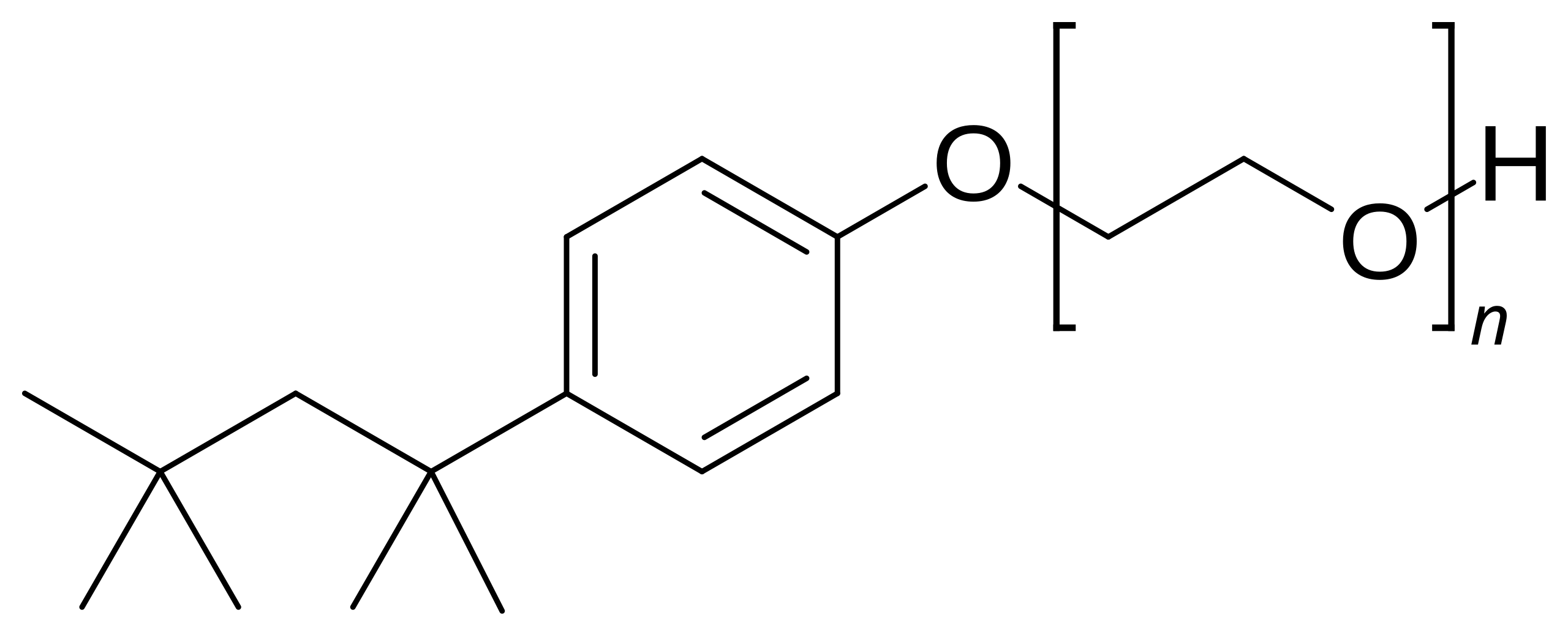

Polyoxyethylene detergents, including Triton X-100, NP-40, and the Tween series, represent an older but still relevant class of non-ionic surfactants. These molecules feature polyethylene glycol head groups of variable length attached to an alkyl phenyl or sorbitan moiety. Their defining characteristic is the cloud point phenomenon—these detergents become insoluble above a critical temperature, which can be exploited for phase separation enrichment of membrane proteins. Triton X-100, perhaps the most famous detergent in molecular biology, remains a workhorse for gentle cell lysis and immunoprecipitation applications due to its mildness and ability to preserve protein-protein interactions. However, significant drawbacks including high UV absorbance that interferes with spectroscopic measurements and heterogeneous composition (commercial preparations are mixtures of oligomers with varying ethylene oxide units) have limited their use in precise biophysical studies. They are best suited for preparative steps and interaction studies where absolute purity is less critical.

Fig.7. Triton X-100

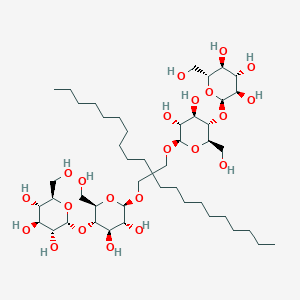

Fig.7. Triton X-100The newest generation of non-ionic detergents showcases rational design principles that overcome limitations of traditional agents. Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG) exemplifies this approach with its innovative architecture featuring two hydrophobic chains and two maltoside head groups linked through a neopentyl glycol scaffold. This branched structure creates exceptionally stable micelles with CMC values as low as 0.01 mM, providing unparalleled protein stabilization. LMNG has been instrumental in determining high-resolution cryo-EM structures of previously intractable GPCRs and large membrane protein complexes. Its cousin, glyco-diosgenin (GDN), incorporates a steroid-derived hydrophobic group, offering even greater stability for fragile complexes. While these advanced detergents come with very high costs and extremely low CMCs that make removal challenging, they have become indispensable for cutting-edge structural biology where sample quality directly determines success or failure.

Fig.7. Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG)

Fig.7. Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG)Zwitterionic Detergents: The Middle Ground

Zwitterionic detergents occupy a strategic intermediate position between ionic and non-ionic classes, containing both positive and negative functional groups that render them net-neutral overall but retain electrostatic character. CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) and its hydroxy analogue CHAPSO represent the most widely used zwittergent family. Built on the cholate steroid skeleton, these molecules combine the mild hydrophobic core of bile salts with a sulfobetaine head group that provides excellent water solubility and protein compatibility. With CMC values around 6-8 mM, CHAPS offers the significant advantage of compatibility with ion-exchange chromatography, a technique normally precluded by charged detergents. This property makes it valuable for purification schemes requiring IEX as a key separation step. CHAPS has proven particularly effective for functional enzyme purification and 2D gel electrophoresis, where its ability to prevent aggregation while maintaining solubility is crucial. However, the same electrostatic characteristics that enable IEX compatibility also make CHAPS harsher than purely non-ionic detergents, and it can still disrupt some protein-protein interactions and denature sensitive proteins.

![CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate)](/upload/images/fig-8-chaps-3-3-cholamidopropyl-dimethylammonio-1-propanesulfonate.jpg) Fig.8. CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate)

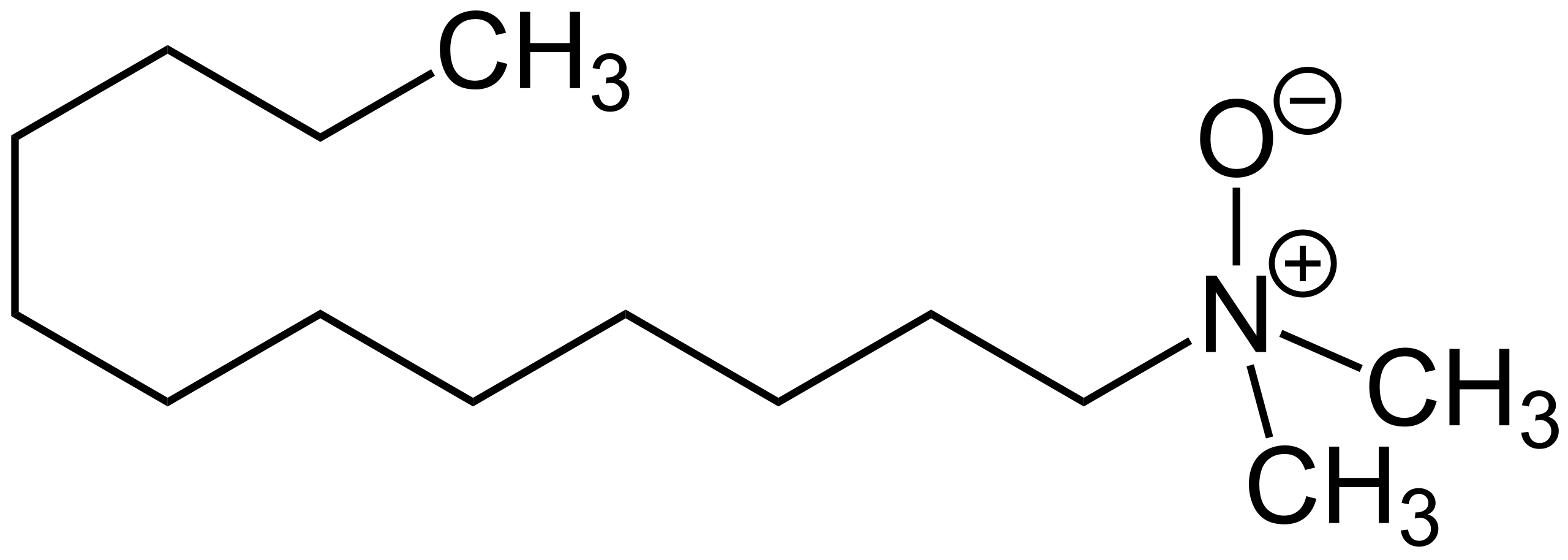

Fig.8. CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate)LDAO (lauryl dimethylamine N-oxide) offers a different zwitterionic architecture with a simpler C12 alkyl chain and an amine oxide head group. This detergent has found particular success in bacterial photosynthetic membrane research, where it efficiently solubilizes pigment-protein complexes while preserving their light-harvesting function. The amine oxide head group is more robust across pH ranges than the carboxylate groups in CHAPS, providing more consistent performance. However, LDAO's effectiveness varies significantly between bacterial and eukaryotic proteins, performing optimally on the more robust bacterial IMPs while sometimes proving inadequate for delicate mammalian receptors. Strategic application of zwitterionic detergents often involves using them as part of mixed detergent systems, where their intermediate properties can bridge the gap between harsh ionic extraction and gentle non-ionic stabilization.

Fig.9. LDAO (lauryl dimethylamine N-oxide)

Fig.9. LDAO (lauryl dimethylamine N-oxide)What are the Key Physicochemical Parameters of Detergents and How Do They Impact Purification Success?

Successful detergent selection and optimization require deep understanding of the key physicochemical parameters that govern detergent behavior. The critical micellar concentration stands as the most consequential parameter, as it determines the concentration range where detergents transition from acting as individual molecules to forming functional micellar structures. CMC values span an enormous range across detergent classes, from the ultra-low 0.01 mM of LMNG to the 25 mM of octyl glucoside. This variation has profound practical implications: detergents with high CMC values can be readily removed by dialysis or dilution, but require higher working concentrations that may approach denaturing thresholds. Conversely, low-CMC detergents provide stable micelles at micromolar concentrations but resist removal, often necessitating specialized techniques like hydrophobic adsorption onto Bio-Beads or detergent-binding spin columns. The rule of thumb for solubilization is to work at 1-3 times the CMC, ensuring adequate micellar mass for efficient extraction while minimizing the concentration of free monomers that can cause denaturation. During purification, reducing to 0.1-0.5 times CMC often improves chromatographic performance by decreasing micelle concentration, provided the target protein remains stable.

The aggregation number—the average number of detergent monomers constituting a micelle—directly impacts biophysical characterization. Small micelles formed by detergents like OG or cholate (aggregation numbers <20) provide minimal size inflation of the protein-detergent complex, enabling better resolution in size-exclusion chromatography and more accurate determination of oligomeric state. However, these small micelles offer less protection to the protein's transmembrane regions. Large micelles from DDM or LMNG (aggregation numbers >50) create robust shielding but increase the apparent molecular weight by 60-100 kDa, complicating SEC analysis and requiring careful column calibration with detergent-containing standards. The micelle size also affects dynamic light scattering measurements and can interfere with crystallization by creating large, disordered regions around the protein. Understanding this trade-off between protective capacity and analytical interference is crucial for experimental design.

The Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) value provides a predictive metric for detergent performance, calculated based on the relative sizes of hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties. The HLB scale runs from 0 to 40, with optimal values for membrane protein solubilization typically falling between 12 and 15. Detergents with HLB values in this range demonstrate the ideal balance of water solubility and membrane insertion capability. Recent advances in rational detergent design leverage structure-property relationships to tune HLB values for specific protein families, creating customized surfactants with optimized extraction efficiency. Additionally, the cloud point phenomenon exhibited by polyoxyethylene detergents, where phase separation occurs above a critical temperature, can be exploited for membrane protein enrichment but must be avoided during routine purification to prevent sample loss. Temperature effects generally follow Arrhenius kinetics, with solubilization rates increasing exponentially with temperature but so does denaturation risk, necessitating careful thermal control, typically at 4°C for functional work.

How to Select Suitable Detergent? A Goal-Oriented Framework

Selecting the optimal detergent requires a systematic, goal-oriented approach that considers the target protein's properties, the intended downstream application, and practical constraints such as cost and sample availability. The selection process begins with a clear definition of the research objective, as this determines the acceptable trade-off between extraction efficiency and structural preservation.

For functional studies requiring native conformation and ligand binding capability, non-ionic detergents like DDM or LMNG represent the primary choice, with CHAPS or deoxycholate serving as backup options if initial extraction yields are inadequate. These mild agents preserve the delicate balance of forces maintaining active sites and allosteric coupling, though they demand careful optimization and may require supplementation with stabilizing additives. SDS and CTAB should be avoided entirely for functional work, as their denaturing potential almost guarantees activity loss.

In contrast, structural biology applications, particularly cryo-electron microscopy, have been revolutionized by the development of ultra-mild, low-CMC detergents like LMNG and GDN. These next-generation surfactants create micellar environments that closely mimic native membranes, enabling high-resolution structures of previously intractable proteins. For X-ray crystallography, traditional workhorses like DDM or even OG remain viable, as crystallization often benefits from smaller, more ordered micelles.

Proteomics and mass spectrometry workflows present a different set of priorities, where complete coverage and digestion efficiency trump functional concerns. Here, SDS reigns supreme due to its ability to denature proteins thoroughly, ensuring complete trypsin accessibility and uniform peptide recovery. The detergent's interference with LC-MS can be mitigated through methods like filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) that remove SDS after digestion. When targeting specific membrane proteins for functional proteomics, deoxycholate offers a middle ground, providing better extraction than mild detergents while remaining compatible with downstream mass spectrometry after proper cleanup. Co-immunoprecipitation and protein-protein interaction studies demand the gentlest possible conditions, making Triton X-100 or NP-40 the default choices despite their heterogeneous nature. These detergents preserve weak protein associations that stronger surfactants would disrupt, enabling the study of physiological complexes. Ion-exchange chromatography, a powerful purification method, is generally incompatible with charged detergents but works well with CHAPS or low concentrations of deoxycholate, opening strategic purification routes that would be impossible with SDS or CTAB.

Related Protein Interaction Analysis Services

Systematic screening remains the gold standard for detergent optimization, particularly for novel proteins or complex membrane systems. A typical screening protocol employs a 24-well format, testing 3-5 candidate detergents at two concentrations (1×CMC and 3×CMC) with identical membrane preparations. Each condition is evaluated for three key metrics: extraction efficiency quantified by Western blot, functional activity measured by a relevant assay (ligand binding, enzymatic activity, or transport), and size-exclusion chromatography profile to assess monodispersity. Plotting these parameters against detergent concentration often reveals a sweet spot where extraction plateaus while activity remains high. This data-driven approach prevents reliance on suboptimal conditions and identifies detergents that may not be obvious first choices. For precious samples, the screening can be miniaturized to 96-well plates with micro-volume assays, conserving material while maximizing information gain. Cost considerations also factor into selection: while SDS and cholate cost mere dollars per gram, DDM commands $50-100 per gram, and LMNG can exceed $200 per gram. For large-scale preparations from bacterial overexpression systems, economical detergents like DOC or OG may be justified, whereas limited samples from primary tissue or challenging expression systems warrant investment in premium detergents to maximize success probability.

| Research Goal | Primary Choice | Backup Options | Avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional assays | DDM, LMNG | CHAPS, DOC | SDS, CTAB |

| Structural biology | LMNG, GDN | DDM, OG | SDS |

| Proteomics/MS | SDS | DOC | LMNG (hard to remove) |

| Co-IP/Interactions | Triton X-100, NP-40 | CHAPS | SDS, CTAB |

| Ion-exchange | CHAPS | Low-con DOC | SDS, CTAB |

| Rapid removal | OG, CHAPS | DOC | DDM, LMNG |

Emerging Trends and the Future of Membrane Protein Purification

The field of detergent-based protein purification is experiencing rapid evolution driven by technological advances and a deeper understanding of membrane protein stability. Novel detergent architectures are emerging from rational design efforts, including fluorinated surfactants that offer exceptional chemical stability and reduced denaturation potential due to the rigid, hydrophobic nature of fluorocarbon tails. Cleavable detergents containing photolabile or pH-sensitive linkers enable on-demand removal by simple light exposure or pH shift, simplifying buffer exchange. Oligoglycerol detergents with multiple glycerol units provide tunable HLB values that can be optimized for specific protein families. These innovations promise to expand the toolkit beyond traditional chemistries, offering solutions for previously intractable targets. However, perhaps the most transformative trend is the development of detergent-free approaches that fundamentally circumvent the limitations of micellar systems. Styrene-maleic acid lipid particles (SMALPs) use amphiphilic polymers to directly extract membrane proteins within native patches of lipid bilayer, preserving annular lipids and local membrane environment with unprecedented fidelity. This technology has enabled functional studies of complexes that were impossible to maintain in traditional detergents, though it requires optimization of polymer-to-protein ratios and is not universally applicable.

Nanodisc technology offers another detergent-free alternative, using membrane scaffold proteins to reconstitute IMPs in controlled, disc-shaped lipid bilayers of defined size and composition. This approach provides a near-native environment while enabling precise control over lipid composition, making it ideal for studying lipid-protein interactions. Amphipols—amphipathic polymers that wrap around transmembrane domains—provide yet another stabilization strategy without traditional detergents. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence is revolutionizing detergent selection through machine learning models like DeepSol and MPNext that predict optimal detergents based on protein sequence, topology, and known biophysical properties. These algorithms, trained on thousands of experimental outcomes, can reduce weeks of empirical screening to days of targeted testing, accelerating research and improving success rates. Looking forward, the integration of AI-driven selection, rationally designed next-generation detergents, and hybrid approaches combining detergent extraction with detergent-free stabilization promises to make membrane protein purification more predictable and successful. While traditional detergents will remain indispensable for routine work and analytical applications, the frontier of functional and structural membrane proteomics increasingly lies beyond the micelle, in native-like environments that preserve the intricate dance between protein, lipid, and water that defines biological function.

Related Products & Services

Resources

-

Enhance Your Biomedical Research With Our High Quality Transmembrane Proteins

-

Transmembrane Protein

-

Mastering Membrane Protein Purification: The Detergent Dilemma

-

Picking the Perfect Detergent for Membrane Proteins

-

Master Detergent Selection in 60 Seconds

References

- Helenius & Simons, "Solubilization of Membranes by Detergents" Biochem Biophys Acta (1975)

- le Maire et al., "Detergents as Tools in Membrane Biochemistry" J Biol Chem (2019)

- Parker et al., "Strategies for Solubilizing Membrane Proteins" Methods (2022)

- Schlegel et al., "Bacterial-Based Membrane Protein Production" BBA (2021)

- Woubshete et al., ChemPlusChem (2024)

- Duell et al., "Ionic Detergents in Membrane Protein Purification" Protein Science (2023)

- Kaipa et al., Protein Expression Purification (2023)

- Knowles et al., "Membrane Protein Stability in Detergent Solutions" Biochemistry (2021)

- Booth et al., "Rational Design of Novel Detergents" JACS (2022)

- Thermo Fisher Scientific, "Detergents Overview" (2025) : Fisher Scientific, "Maltoside Detergents Technical Guide" (2025)

- Nature Communications, "Triglycerol Detergents" (2025)

- HAL Archives, "Membrane Protein Purification Thesis" (2022)

- Glasgow Theses, "Bacterial Photosynthetic Complexes" (2021)

- Bio-Review, "Mitochondrial Protein Extraction" (2025)

- ChemRxiv, "Membrane Proteins as Biotherapeutic Targets" (2024)

- Bibis.ir, "Protein Purification Textbook" (2022)

- Ratkeviciute et al., "Membrane Protein Purification Pipeline" Protein Science (2021)

Contact us or send an email at for project quotations and more detailed information.

Quick Links

-

Papers’ PMID to Obtain Coupon

Submit Now -

Refer Friends & New Lab Start-up Promotions